And so again we wait. Two years later, to the exact day, my wife, Carly, and I find ourselves in the same position we were in during those late winter days of March 2021: waiting for the arrival of our child, for the moment our world will shift and our lives will change. The result of that first wait, which ended 11 days after the due date, was nothing less than the light of our world, a strong little girl with a perfectly round face named Mayla.

You’d think I’d be better equipped, then, for this time. I am not. If anything, it’s worse. We were convinced that this baby, for whom we do not know the gender, would come early—that’s what they say about your second, right? The path has already been trodden by their older sibling, so they just come whenever they want, and invariably that’s before their due date, right? We’d definitely have a February baby this time, we told ourselves, no way that both babies would remain in Carly’s stomach well past their due date. No, we thought as the calendar turned from January to February, this baby was coming in a couple days, weeks at most. This baby was coming soon!

They were not. Carly thought she might be in labor the morning of Feb. 13, with intense contractions not far apart. The app on her phone told us to get our bags ready to head to the hospital; she started drafting an email to her supervisor, telling her that she’d be out of work earlier than planned.

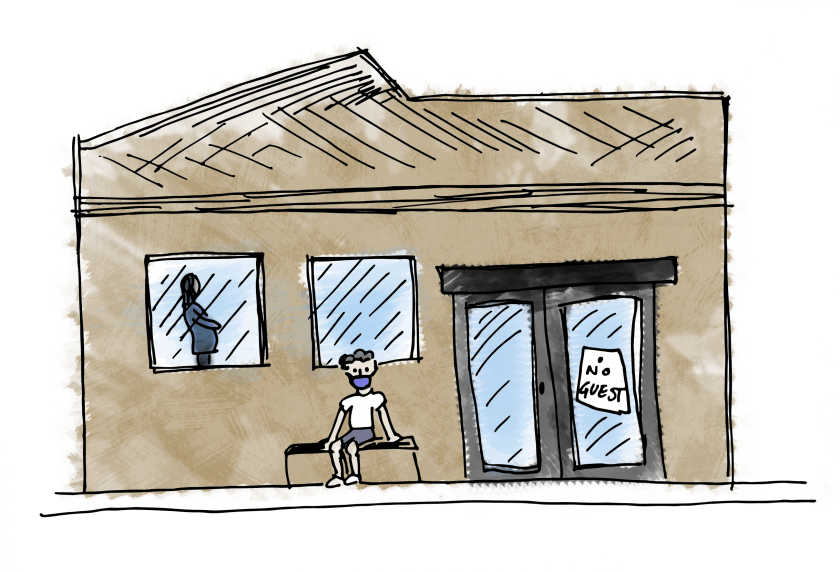

It is now March 6. That means every day for the past 21 I’ve been wrestling with the notion, the burden, that today could be the day. The expectation, more than anything, has wrecked me. I’ve been more stressed than necessary, and highly irritable. Every decision, from when to give my fifth graders a science test to what time I should run the next day, seems enormous, way more significant than it should be. Scheduling anything has come with the caveat that my wife could go into labor so I might have to miss it. I’m scared to be away from my phone for longer than five minutes. Every day is a swirling cocktail of emotions, of hope and excitement mixed with embarrassment and disappointment that I’m disappointed the baby hasn’t yet arrived. One day last week when I woke up Carly was unsure if I should go to work that day: She had been having consistent, strong contractions and didn’t want me to just have to turn around. I drove to work, convinced that in a few hours I’d be driving in the opposite direction, ready to experience a momentous life change. Nothing happened. Life continued that day as usual, save that I was carrying a nervous excitement-turned-disappointment in everything I did.

The problem, of course, is not with the baby or Carly, no matter what some comments might lead us to believe (“Why hasn’t your wife had this baby yet?” “Why isn’t this baby here yet?”—as if they have autonomy). No, the problem is my, our, society’s expectation of babies arriving when they “should.” We are told, then conditioned to believe, that babies have a due date, and if, like a gallon of milk, they go past that date, they are considered “late.” If they come before it, they’re “early,” and if they are one of the rare few that are born on their due date, they are “on time.” Babies, in this view, are simply packages delivered by Amazon, or a stork.

As soon as the due date comes—I honestly dreaded it this time, because I knew what was going to happen in the following days—people from all areas of your life will pepper you for updates, look at you incredulously when you walk through the doors of your work, ask when the induction will be, greet you with “What are you still doing here?” All of it will be good-natured and well-intentioned, and you will do your best to smile and offer short, simple answers. And you will be grateful, ultimately, that you have a baby coming at all, forever aware that a child, your child, is a miracle. Plus, you understand that in their eyes, the calculus is simple: The baby was supposed to be here already, the baby is not here, what’s up with that? A baby coming a week past their due date doesn’t align with their expectations of how it should have happened (“No baby yet???? They’re so overdue. Wonder if they’ll ever come!”), and so they want to know why, and they will ask you. You will want to go somewhere, anywhere, to escape the burden of waiting. Instead, everywhere you will be bombarded with the same questions that you’ve been wondering about yourself for the past month. Perhaps what people don’t realize when they ask those questions is that, trust us, we’ve been asking, thinking about, the same ones. We do not suddenly remember that our child hasn’t been born yet when someone asks us. It’s occupied every neural bandwidth we possess for several weeks. There is no one that a “late” birth affects more than the parents of the child. We are trying to be patient.

So therein lies the conflict: Society dictates that a baby is late if they’re not here by their due date, but the baby doesn’t know or care about when they’re “supposed” to be here. They don’t care that you want to get one more decent night’s sleep, or finish up the next project at work, or have another lowkey weekend. They don’t care about people’s expectations about their arrival, including their own parents’. They don’t care what’s most convenient for you, or for the people who ask you. They will arrive when biology dictates.

Mayla was born 11 days late. In the past two years—which have been among the best of my life, watching her grow into a beautiful and independent and hilarious little girl—I have thought about that fact exactly zero times. When your child comes does not matter, not really, in the grand scheme of things. So long as they and their mother are healthy and safe, the timing, the due dates and questions and expectations—all of it is irrelevant. The most important truth is the most simple one: We will have a baby in our arms, soon.

And so again we wait. The moment will come when our child enters the world and changes ours forever. And right then we will know that they came right on time.