One Friday night over a year ago, my wife, Carly, and I picked up dinner from our favorite barbecue restaurant. She ordered pulled pork; I got chicken wings.

We were, as first-time parents to a 4-month-old named Mayla during scary stages of a pandemic, exhausted and probably too excited about our once-a-week takeout meal: a chance to sit on the floor of our living room, eating food we didn’t have to prepare from our coffee table and watching a familiar, comfortable TV show—just the two of us, like old times in old places. These meals were refreshing and necessary, some of my favorite times of the week.

All we had to do was get Mayla to bed.

Perhaps more than anything else, bedtime—that nightly journey to help your child find sleep—has demonstrated how much Mayla has grown up, and how much she has changed.

Before I became a father, bedtime was simply a couple-of-steps routine that I did almost automatically: brush the teeth, read or mindlessly scroll through the phone, turn off the lights. Once we had Mayla, though, I learned that it was something far greater: Bedtime is a significant part of the day, like mealtime and naptime and playtime. It is scheduled and, because I’m married to an extremely organized woman, scripted, written out in steps on the white board that hangs in our hallway. Bedtime is an event.

And for the first five months of Mayla’s life, it was an event that she hated with a burning passion. We would, our little family, be having a pleasant evening and Carly and I would be thinking that, hey, maybe parenthood isn’t that hard, maybe we’re doing OK—and then 7:30 or 8:00—bedtime—would come around and everything would fall apart. Mayla would scream as we carried her up the stairs to the nursery, scream as we put her pajamas on, scream (louder now) when we dimmed the lights and turned on the sound machine, scream as we sang a soft lullaby (the contrast was striking and borderline comical), and scream, especially, as we lay her down in her crib (or bassinet during the earlier months) to sleep. And this wasn’t one of those halfhearted, I’m-going-to-see-if-I-can-get-what-I-want screams; this was a full-throated, visceral shriek of intense displeasure. She’d do this for upwards of an hour some nights. Bedtime was awful.

Hypotheses about why she so despised it abounded: We thought, for a while, that maybe because she had cried the first few times we implemented a structured bedtime routine she had, like Pavlov’s dogs, become conditioned to dislike it thereafter. We thought that maybe she was experiencing a very early and strong feeling of FOMO, that she didn’t want to go to bed because she wanted to hang out with her parents and keep exploring this grand new world. We thought that maybe she just didn’t like the dark.

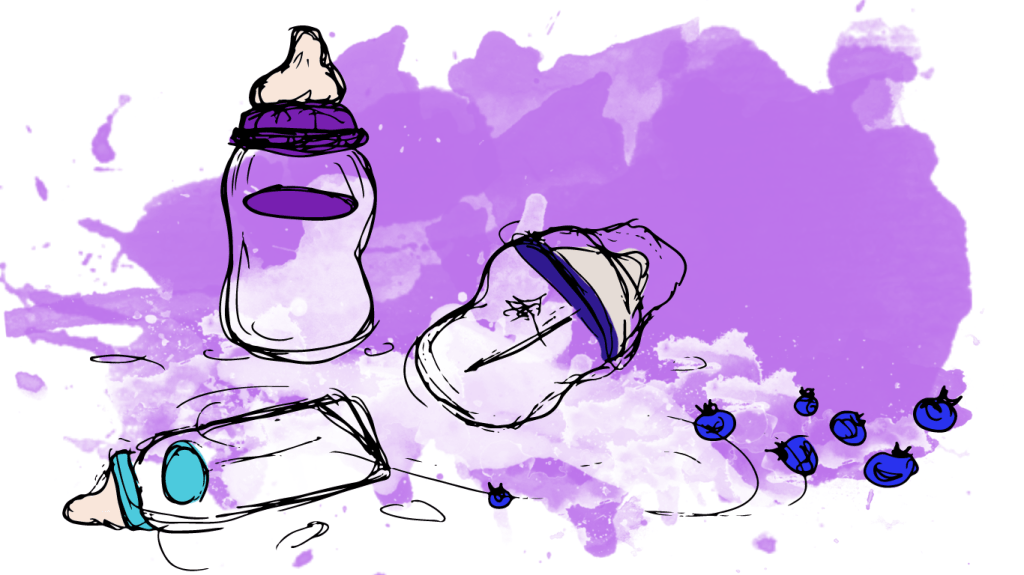

(The likely truth was actually much sadder than any of these guesses: We had an extremely challenging time feeding Mayla, centered mostly on her inability to take a bottle, and we realized later, once she could finally drink from one, that she was probably just hungry. Carly had fed her as much as Mayla would take given her tongue and lip tie—would feed her for hours every day and exhaust herself physically and mentally—but Mayla still couldn’t get enough.)

Pretty soon we stopped thinking at all. We were drained. Bedtime soon became a trigger not only for Mayla but for Carly and me as well. As soon as the evening started winding down, as soon as the summer sky would turn a soft blue-gray, I’d get that sinking feeling in my chest: Bedtime was coming, and it wasn’t going to be pleasant.

There were very few times I was incorrect with that assessment: We’d go through the routine—PJs, lights, sound machine, lullaby—that had become a drudgery and Mayla would cry the entire time. Carly would rock her in her arms for sometimes a half-hour (or approximately 20 renditions of “Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star”) before being physically incapable to continue and passing her off to me. I’d sing and rock and sway and do everything I could think of to try to calm her down, and Mayla would simply scream into the dark.

It was, of course, intensely frustrating and I think we’d both admit, not proudly but honestly, that some small, ugly part of us began to resent our baby daughter. To us, it seemed so simple: Just go to bed! We both, at that point, would have given away a vital organ for precious sleep, and here she was refusing what we craved more than anything. We knew that thinking was wrong and bad, that she was simply a baby and was trying to communicate in the only way she knew how, but we were, like most first-time parents, confused and tired.

When someone, usually Carly, was finally able to get her to calm down, to stop crying and close her eyes in her mom’s warm arms, the real challenge began: to lay her down without waking her up. Carly would lean over the edge of the crib and slowly, so slowly, lower her arms. If Mayla made even the slightest movement Carly would pick her back up and start the process anew. When she got her down on the mattress, perhaps after two or three tries of this first step, she then had to extract her hands from underneath Mayla. Removing her hand from behind Mayla’s back was typically straightforward, but moving it from under her head was entirely more complex: Carly had to use her other hand to delicately lift Mayla’s head to give her head-holding hand the space to move out, and then lay her head back on the mattress without letting it roll to the side or land too hard, because either would wake her and render the entire process worthless. Watching her do this—as I usually did, sitting in the dark corner of the nursery—was like watching a doctor perform open-heart surgery, so precise was her every move. Mayla woke up during this process more often than not, and it was those nights that we felt truly defeated.

That Friday night when we ordered takeout was one of those times. Mayla screamed for what seemed like hours, before finally calming down but then waking up screaming when Carly tried to lay her in the crib. This happened at least three times. We were in the room for close to two hours before our daughter, miraculously, went to bed.

The barbecue was cold when we ate it later.

Mayla loves bedtime now. When, after dinner and post-dinner reading or swinging or block playing, we say, “OK, it’s time to go get ready for bed!” our daughter’s face will light up as she points toward the ceiling to indicate that she is ready to go upstairs. Often she will climb up by herself and other times she asks to be carried, and thus begin bedtime.

First, we brush her teeth—with a squeeze of toothpaste the size of grain of rice—ourselves before allowing her to try by herself (which she does with a smile but very little teeth cleaning). She then loves to exclaim “Wawa!” to identify the clear liquid falling from the sink, and giggles as it gets her feet wet in the sink. Next we try to wrangle her into some pajamas as she laughs and squirms and talks and holds both of her stuffed babies in either arm. The only passing sign of displeasure is when we have to apply cream or moisturizer for rashes or dry skin.

Then she waddles over to her basket of stuffed animals to get them in place for reading time, taking each one out and handing them to whichever one of us is sitting in the rocking chair, where we are now surrounded by at least three stuffed bears, two elephants, a llama, and a flamingo. Only when everyone is in place does she choose two or three books for us to read, specifying which one is for Mama and which is for Dada, before (sometimes) sitting and (less often) listening attentively as we read about mice and bears and little girls named Madeline getting appendectomies. When the books are finished, she invariably tries to ask us to read more, which she would do until midnight if we let her.

When reading time is over, we tell her to put her animals away—most go back in the basket, but she sleeps with one of the elephants, so he goes over the crib railing—and we once asked if she was going to put her babies in bed, too, but she shook her head no, and now she does that every night whether we ask or not. So she holds on to them tight.

Finally, we lay out her sleep sack on the floor and say, “OK, it’s time for sleep sack!” And our daughter, who used to cry as soon as we carried her up the stairs to her room for bedtime, lays down on the floor on her own accord because she wants to go to bed.

Bedtime is genuinely enjoyable now, a pleasant conclusion to Mayla’s day and the beginning of our precious hours of relaxation before we go to bed ourselves.

Once Mayla is in her sleep sack, Carly rocks her in the chair as we say our prayers and she rubs her eyes, yawns, and leans over to both of us for kisses (and often holds up her babies so we kiss them, too). Once we say “Amen,” I tell her she is beautiful and I love her to the moon and back, and before I close the door on the way out, I look back into her deep blue-green eyes, sleepy and serious. I relish the fact that the last thing my daughter sees before the lights dim is me blowing her kisses.

Carly comes out of the room a few minutes later, and together sometimes we watch, from the baby monitor, Mayla hug her elephants and dolls and shift her body dramatically to get comfortable, and we marvel at how far she has come, how far we have come, how our daughter is growing up, and that fills us with a strange mixture of pride and nostalgia, nostalgia for those long loud nights and cold barbecue, when she needed us to hold her, and pride that she made it, we made it, our little family is making it, and we both just stand there with silent smiles.

Join our mailing list!

Subscribe to the Essays of Dad newsletter, a weekly email with parenting stories, background on essays, book recommendations, and more.