We, as parents, are supposed to teach our kids about the world: what’s good and bad and everything in between. We’re supposed to provide them a structure and framework by which they can begin to understand its complexities and ask questions when they don’t. We’re supposed to help them shape and sharpen their perspective and challenge it when necessary. We’re supposed to be their guides.

But through 18 months of being a dad to Mayla, our strong, hilarious, stubborn little girl, I’ve learned that the opposite is true, too: Our kids can teach us. I’ve learned—or perhaps relearned—things from Mayla that are as or more valuable than anything I’ve taught her.

So here’s to those timeless lessons of toddlerhood. May we all remember them when life gets crazy.

- Take your work seriously.

Recently Mayla has become a chore connoisseur. If you ask her to open the door to let the dogs in, she immediately stops what she’s doing and marches over to it, stretching her arm and standing on her tippy toes to pull the handle. If you hand her a piece of trash and ask her to throw it away, she opens her hand and takes it to the trash can in the kitchen. If you open the dishwasher, she’s suddenly at your side, taking spoons out of the silverware hatch and handing them to you to put in the drawer (which she’d do herself if she were tall enough). If you say it’s time to feed the dogs, she scoops up the dog bowl and heads over to the bin of food in the pantry, waiting expectantly for someone to scoop a cup in. Then she carries over the now-filled bowl to the dogs’ designated eating spots, invariably dropping some (or a lot) of food along the way. When this happens, she immediately sits down and silently picks up every piece of dropped food, one by one, and places it into the dog bowl. It is attention to detail at its finest.

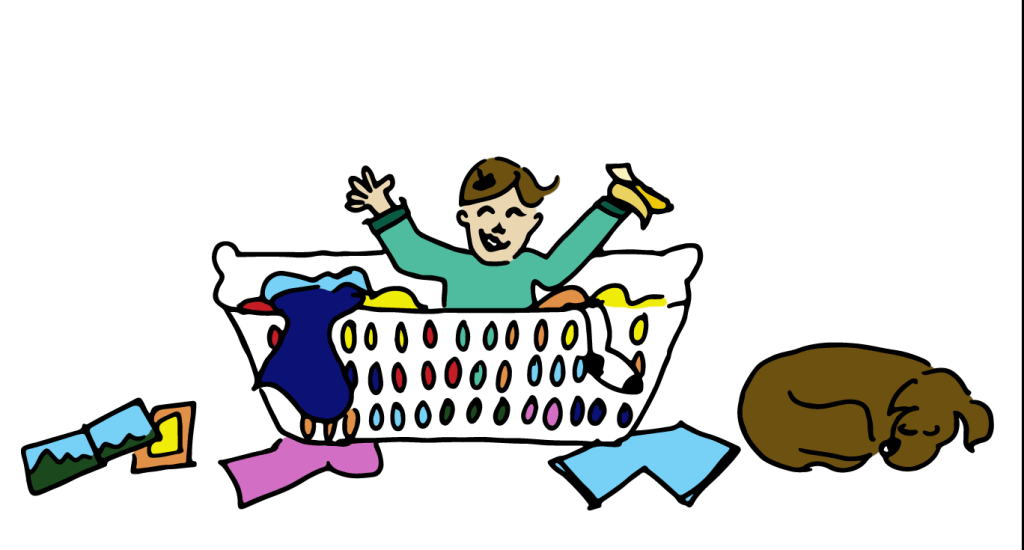

By far my favorite, though, is laundry. First, she loves to help put the dirty clothes into the machine, taking care not to miss even the smallest sock, helps scoop and pour the detergent, and presses the power button to begin the cycle. Then she goes about her day—until she hears the washer chime to signal the cycle is complete. She immediately drops whatever she’s doing, points over to the laundry room, and exclaims, “Uuahh!” as a giant smile forms on her face. This is our signal that she wants to move the clothes to the dryer, which we then do together. Finally, once all of the clothes are clean and dry (another chime that elicits a joyful scream), she helps us sort and organize all of them as we put them away in our bedroom.

My favorite part about all of this is the look on Mayla’s face when we ask her to do one of these tasks: She looks us directly in the eye, unsmiling, as if to say, Thank you for trusting me. I won’t let you down. To us, they’re relatively menial, quotidian chores; to her, they’re the most important thing she’ll ever do, and she treats them as such. I love that.

- Play. Every day.

Work, as Mayla has established, is important. But so too is play.

Most of Mayla’s non-eating waking hours are spent playing: at the park, on the swing Papa built her in our backyard, in the playroom upstairs. She loves to play with blocks and cars and ramps and balls and bubbles. She loves to play hide-and-seek and chase and (an extremely basic form of) soccer. She loves to play with her Mama and Dada and grandmas and grandpas and aunts and uncles, with anyone who will pick up some blocks and help her make a tower. She loves to play.

Life, as we all know, is busy, and fulfilling your responsibilities as a parent or spouse or employee is of course paramount. But perhaps we should not forget to make time for, every day, something that brings us that simple, pure joy we found every day as kids.

- Food is life. Treat it as such.

Since we had such a challenging time feeding Mayla as an infant, we were worried that we might also have trouble when she graduated to solids. We did not.

Mayla loves to eat. Breakfast, second breakfast, lunch, post-nap afternoon snack, pre-dinner stroller snack—these are, probably, her favorite times of the day. It starts in the morning, soon after she wakes up, when she’s strapped into her high chair, wrapped with her bib, and gets to work. She eats eggs or waffles or oatmeal or yogurt (or sometimes several of these at once) and always, always fruit: blueberries and bananas, mostly, but often also strawberries and blackberries and oranges. It is her biggest and best meal of the day.

The rest of her day is dictated by her eating schedule, and she will, by rapidly moving her bunched fingers toward her mouth, sign language for “eat,” let you know when it is time for her next meal. She’s the queen of snacks—Cheerios and cucumbers and cottage cheese—and loves to feed herself independently. If she likes the food you offer her, which is most of the time, she will sign for more and say, “Muuahh!” so adorably that you will have no choice but to agree to her demands. At some meals she will eat more than her mother. If she doesn’t recognize what’s on her plate, she lets us know, usually by pointing at the unidentified food and saying, “Uuahh?” Only when we have identified it all—“black beans,” “rice,” “avocado”—will she begin eating.

Mayla does not understand all of the hype about fad diets. She does not skip breakfast. She does not believe in intermittent fasting. She is not picky or demanding; if it’s in front of her, she’ll try it, and probably like it. She loves going to the farmers’ market and the local ice cream shop. When she’s there, she often treats herself to bites of her parents’ ice cream and doesn’t feel guilty about it. She does not think eating healthy is as difficult as adults sometimes make it seem. She abides by an eating philosophy radical in its simplicity: Eat good food and enjoy it.

- Sometimes all you need is a nap.

Mayla does not pretend to be perfect. There are times when no amount of work, play, or food will fulfill her. During these times she simply needs what most of us crave every afternoon: a nap. A good, dark-room, fan-on, A/C-down, uninterrupted nap. When she wakes up she is refreshed and happy and ready to explore again.

- Pet your dogs.

- Read, often.

If Mayla is not eating, sleeping, playing, or working, she’s likely reading a book. She has her favorites—Blue Hat, Green Hat; Brown Bear, Brown Bear, What Do You See?; Will You Be My Sunshine?—but is willing to try new ones, too. She loves the rhythm of the words and simple beauty of the illustrations. She loves pointing at pictures of things she recognizes, like “buhh”s (birds), “duahh”s (dogs), and “wawa” (water). She reads probably a dozen books a day, at all times of the day. Books, Mayla has reminded me, are sometimes the only entertainment we need.

- Go outside when it’s sunny.

- Go outside when it’s raining.

Mayla is not brought down by the presence of rain; she is energized by it. As soon as she sees water falling from the sky, she excitedly points outside and exclaims, “Wawa!” She then relentlessly asks to go outside, and we eventually must let her, such is her desire to go play in the rain. When she gets her wish, she toddles around through the wet grass and splashes in puddles and raises her arms up to catch the miraculous wet drops falling from above. Her joy in these moments is pure.

- Expressing your feelings and communicating are important.

Mayla has big feelings, and she does not shy away from sharing them. When she is happy, we know. When she is sad or angry, we know. When she is confused, we know. There is something refreshing in knowing exactly what she’s feeling at any given moment, because even if we can’t do something to immediately make her feel better, at least we understand and sometimes that’s all that matters. Carly, my wife, is especially adept at helping Mayla navigate her feelings. “I see that you’re sad,” she’ll tell our daughter. “But we are about to eat dinner, so I don’t want you to fill up on more Cheerios.” Sometimes simply the soothing sound of her mom’s voice will help her become calm; other times it won’t, but Mayla will know that her feeling was identified and understood.

At some point as we grow up we are conditioned to hide weakness, to hide those big feelings, and sometimes that makes it difficult for others to understand. Mayla has reminded me that emotions are real and it’s OK to share them. We don’t have to be perfect. We just have to be honest.

- The world is a vast, beautiful place.

My 18-month-old daughter thinks it’s an absolute joy to be alive. Sometimes she can’t believe that she gets to, every day, explore the world. She thinks it’s a privilege to watch birds fly and rabbits run and water rush through the creek. She thinks every rock on the ground and every airplane flying above is a joy, a miracle. She doesn’t take for granted that she gets to splash in puddles and read books and play with toys. She appreciates the simplicity of walking the dogs around the neighborhood and pointing up to the mountains along the way. She is endlessly curious and endlessly happy.

I love her.

Join our mailing list!

Subscribe to the Essays of Dad newsletter, a weekly email with parenting stories, background on essays, book recommendations, and more.