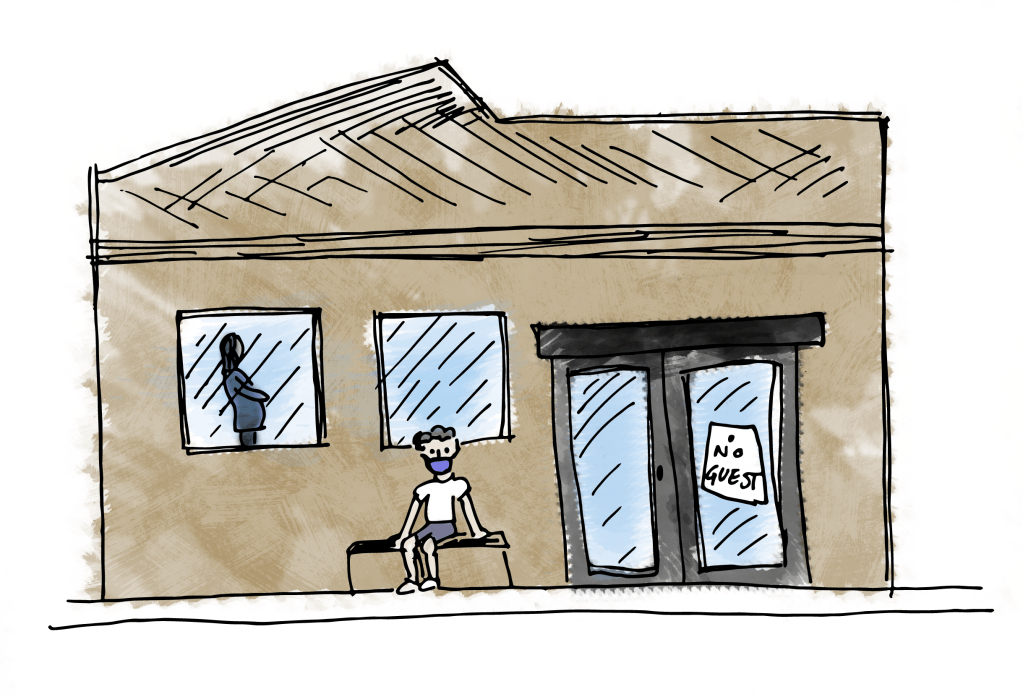

Every Thursday for about a month, I sat alone in my car, staring at the red-brown bricks of a birth center. My pregnant wife, Carly, was inside one of its rooms, being poked and prodded and tested to ensure she and our daughter were healthy and strong. To minimize risk during the worst stages of the pandemic, partners were not allowed in. Sometimes the appointments were quick, lasting no longer than 20 minutes; other times I sat alone for a couple hours.

During these solitary moments, I always noted my view from the car: those bricks, lots of plants, a thin gray tree. We’d been to the birth center so many times, and I’d sat by myself in the car so many times, staring at the same pieces of the world, that we saw winter transition to spring: By the end, the day before our daughter, Mayla, was born, the sad gray tree had started sprouting little white flowers.

The symbolism—our baby coming into the world as flowers began to bloom after a long winter—was not lost on me. Carly and I, on long, cold walks around our neighborhood, would talk about how everything, soon, would be different: We would have a baby girl, and the days would be longer and warmer, and summer break was on the horizon, and we could visit family and friends, and the world, for so long dominated by a stubborn pandemic, would return to some type of normal (or so we thought). On the best days, we were filled with hope.

For the last three-plus months of the pregnancy, that’s all we had. Alarmed by stories of mothers-to-be facing more severe COVID cases, and with vaccines unavailable for us until the early spring, we were, more than most, locked down. We worked from home. We bought an annual subscription to Instacart and used it weekly. We ordered delivery, asking drivers to leave the food at the door; if we were feeling adventurous, we got takeout, our lone semi-weekly venture into the world. Those trips inside the restaurant terrified me, even as Carly stayed in the car. (One night, a week or so before the due date, I spent the better part of three hours worrying if I got COVID from a maskless woman chasing her daughter around a restaurant where I was waiting for food.) I used to half-jokingly tell my friend, also an expectant father, that if everyone in the world had a pregnant partner, the pandemic would recede in days.

Carly, to her credit, rarely complained about the hand she was dealt. She had looked forward to pregnancy, and motherhood, for most of her adult years, and this pandemic pregnancy of course did not live up to her expectations; but she maintained, better than most, perspective: She knew that her, and our, problems were minor held up against the ones affecting hundreds of thousands across the country and world.

We, like everyone else, made sacrifices to keep our family safe. Carly had wanted a big baby shower; we had one on Zoom and another with three friends sitting in spaced-out chairs in our backyard. She wanted to go home to Florida for Christmas to spend time with family and show off her growing bump; we ended up, to minimize risk, staying by ourselves in North Carolina. She wanted to attend in-person childbirth classes, to meet other moms, to feel connected to a community; she was, for weeks and then months, basically alone.

That included all of her appointments: The first time I was allowed in the birth center was the day Mayla was born. In the car I cried only once, on week 41, when she had to go to a different building for a different test; maybe I missed my familiar bricks and tree. Remaining by myself in the parking lot was a small price to pay to protect nurses, doctors, and mothers, but I wanted desperately to be in the room with her, holding her hand and watching Mayla squirm on the little black-and-white screen. The first time I saw our daughter, at the 20-week ultrasound to confirm her heartbeat, was via FaceTime as I sat in the parking lot.

A lot of it, to use the formal phrase, really sucked. But the most important truth never changed: She and Mayla remained healthy for nine-plus months. And this spartan existence, with just the two of us spending together lazy days and slow nights, was perhaps the one of the best ways to culminate our pre-parenthood lives. We would work, at home, until mid-afternoon, go on a walk around the neighborhood as the sun slowly sank below the mountains, talking about the baby and plans and the world. When we got back home we’d stretch in the living room, listening to music and playing with the dogs, before making something warm for dinner and eating it while we watched “New Girl.” Then we’d clean up and get ready for bed, without rushing, and watch TV or just sit there, talking and marveling at Carly’s moving stomach, letting it sink in how wild, how wonderful it was that there was a baby, our baby, in it; and she would drift off to sleep, and I’d read with the lights out before joining her in dreaming.

Now, of course, when life has sped up and responsibilities have multiplied, we both miss those unhurried days. Now we work and coach and come home and work some more and eat dinner and pack our lunches for the next day and wash bottles and give Mayla a bath and then put her to bed and by the end of the day we’ve seen her, and each other, for two, maybe three hours. And then we do it all again the next day.

Our pandemic pregnancy was stressful and isolating and restrictive. But it was also, toward the end, peaceful, maybe even necessary. We were forced, by circumstance, to return to basics, to prioritize what was essential and forget all else. We were forced to confront a truth that deep down we knew but the rush of life had complicated: that simplicity—family, and food, and books, a warm sun and laughter—is all we really ever need. Everything else is periphery. There is always time to do what matters.

So every time I see a pregnant woman now, keeping a baby alive in the throes of a pandemic, I say a little prayer of protection, and hope that she can find peace amid all of the chaos. I appreciate her, and her partner, sitting alone in the parking lot, staring at bricks, on a deeper level than I ever thought I would.

Join our mailing list!

Subscribe to the Essays of Dad newsletter, a weekly email with parenting stories, background on essays, book recommendations, and more.

4 thoughts on “Lessons from a Pandemic Pregnancy”